Ken Purdham

Bachelor of Arts History & Politics

Diploma of Professional Writing & Editing

Glass River Memories

Recently, when talking about By the Banks of a Glass River, it set my mind back to why I originally wanted to write the story. It’s a story that has everything, including success and failure, tragedy and folklore; and its own ghost.

In the late 1980s Senior manager, Don Thorrington stepped out of his office and growled at me, ‘Ken, come in here!’ Oh, now what have I done, I thought? I’m in strife again, for sure. He was one of those managers who ruled his kingdom with an iron fist, didn’t take fools gladly, and was fearless when defending those under his charge. I was an instrument and controls electrician.

Close to retirement, Donny was cleaning out his office and it was a great relief when he handed me two books. The first book was a technical manual on glass making. I’d clearly been asking too many questions. Why do we have stirrers? why do we set them in UDL, or UDR or squeeze? and why do we have a six volt battery connected between the waste pipes and the furnace superstructure? I must have been a real pain in the … The other book was a special edition of the history of Pilkington Brothers 1826 to 1926. Although I didn’t realise it then, I was destined to tell the Pilkington Australia story and that book was to be my launching pad.

The Pilkington glass making plant was a great place to work where many of us grew

up together. As such it was as much a community as it was a workplace, so it was

always in my mind that I would write a social history; not so much about how we made

glass but how we worked together while making the see-

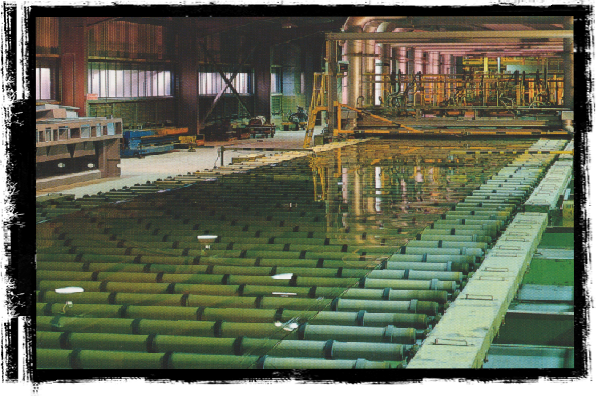

The process starts with a batch house where the raw materials are mixed. Beyond that, there’s a hot end where the raw materials are melted then poured onto a bath of molten tin where it floats as it’s pulled and stretched into a river of glass. The glass then flows through an annealing chamber and into a cold end where it’s cut and stacked as required. In all, just over half a kilometre long.

It was fascinating to me that the people in each of these areas didn’t mix. They were like small tribes living along the banks of a glass river. Those who melted the raw materials had little to do with those who cut it once it was glass. As it was with those who laminated it, toughened it or double glazed it. The trades people traversed each of these areas, trading their fixing skills, as it were, and to me, they were the nomads of the glass river.

The fun part and folklore so often came from individual workers making a lasting

impression, as when Billy, the trades assistant, drove into the factory to be rescued

from his girlfriend’s wrath by his workmates. She had turned up to his place one

night while he was having pleasant dreams with another girl. She sprayed the windows

of his car with paint as he slept. Never to be forgotten, was the jaw dropping reaction

of his workmates as he drove through the factory gate with his car covered in paint

and him peering through a small clear patch scraped into the windscreen. As his mates

got out the paint remover, the cost of Billy’s ‘bit-

When Stan the cleaner died he first appeared as a ghost when a security guard fell

asleep in the first-

The glass river saw the tough times as well as the good times. In the period of the

1980s life was so good, we couldn’t make enough glass to supply the market. Workers

could and did make lots of money while elsewhere people were struggling with 11 to

18 percent interest rates. Then the 1990s brought a recession and the need for restructuring

of the glass making communities. Twenty-

But still we were a glass making community of tribes. Senior manager, Dierk Meyer-

And that community ethos saw us through the gas crisis of 1998 when other furnaces

around Victoria were collapsing because there was no gas to fire them. Side by side,

demarcations put aside, workers and management kept the glass river flowing by converting

our gas-

When we faced the new millennium, the great fear was that we could be shut down by the Y2K phenomenon affecting the instrument controls. People were saying it’s such an unknown even planes could fall out of the sky. When you have a furnace humming along at 1600 degrees centigrade and a float bath of molten tin at between 1100 and 600 degrees, a loss of instrument control could destroy the place. A furnace falling in with 400 tonnes of molten glass spewing everywhere was unthinkable.

As the midnight hour approached, we stacked the glass river with double shifts, called ourselves the Y2K team and waited. Nothing happened. ‘What a damp squib!’ said Tom Hughes the Plant Manager while supervisor, Bruce Tyzac lit the portable barbeque in the lunchroom. But as the sausages began to sizzle, the lunchroom filled with smoke engulfing Bruce and the barbeque. Bloody Hell! The last thing we thought would be brought down by Y2K was the barbie. As a team of heroes, we ran into the smoke, dragged out the barbie and then Bruce and were able to suck on our sausages alongside the glass river that had kept on flowing without a fuss.

The Pilkington story ends in 2008 when the business was sold off to others. But the glass river still continues to flow, even in these tough times and under different ownership and is arguably still the best quality glass you can by anywhere.